13 January, 2025 | Author: Professor Robyn Jamieson and Retina Australia

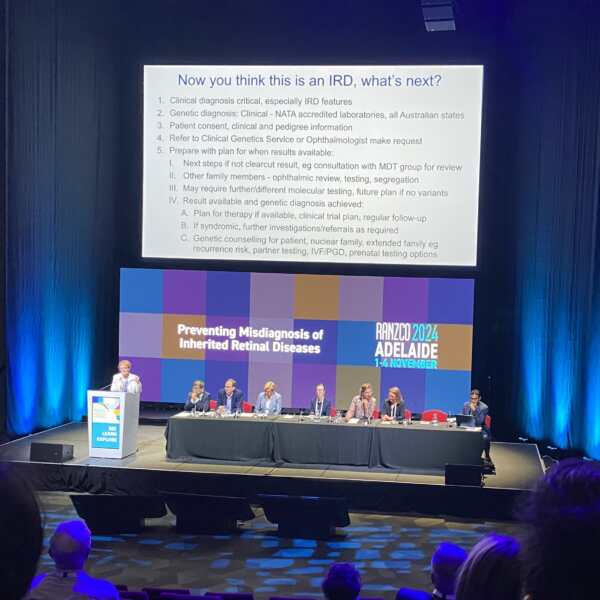

Following on from our previous summary article on Professor John Grigg’s RANZCO Congress 2024 presentation titled “Field Defects: When to Suspect an IRD“, you can now read a summary of Professor Robyn Jamieson’s presentation titled “Now you think this is an IRD, what’s next?”

Genetic testing for inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) is complex due to both clinical and genetic heterogeneity, requiring a meticulous and often multidisciplinary approach. The process starts with collecting detailed patient information, including clinical phenotype and family history, and selecting appropriate genetic tests (such as gene panels or whole exome sequencing). These tests generate vast amounts of data—e.g., analysing over 600,000 data points for 500 genes—necessitating advanced bioinformatics tools to identify potential disease-causing variants.

One challenge is that many variants are still not fully understood, and often several candidate variants may be identified, requiring careful manual review. Geneticists apply established criteria, such as those from the American College of Medical Genetics, to assess the likelihood of each variant causing disease. Sometimes, this requires collaboration within a multidisciplinary team (MDT), including ophthalmologists and geneticists, to interpret the results in light of the patient’s clinical symptoms.

Genetic testing may not always yield clear answers. For example, certain genetic regions, like the RPGR gene associated with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, may not be well-covered in standard tests, leading to missed variants. Additional techniques, like Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or microarray testing, may be needed to detect copy number variations or deletions that are not captured by conventional sequencing.

The process can uncover unexpected findings, such as additional genetic conditions that may affect family planning or pregnancy decisions. This can be because patients may have a previously unrecognised syndromic form of IRD, or may have another condition such as a metabolic disorder in addition to their IRD. This emphasises the importance of pre-test counseling, patient consent, and a clear follow-up plan, including possible genetic counseling, additional testing for family members, and consideration of clinical trials or therapy options.

Genetic testing for IRDs requires careful planning, the use of multiple diagnostic tools, expert interpretation, and a thorough understanding of the patient’s clinical and family history. Collaboration among specialists and a patient-centred approach are essential for navigating the complexities of genetic testing and ensuring the best outcomes.

Case study

A 25-year-old woman, planning pregnancy, experienced decreased visual acuity and other visual symptoms, including difficulty adjusting to changes in light, particularly at night. She had a history of myopia and astigmatism, having worn glasses since age 6. After visiting a GP, she was referred for genetic investigation for retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Genetic testing revealed two heterozygous variants: one in the ABCA4 gene, and another in the CEP290 gene. The clinical geneticist considered whether these variants could explain her symptoms. The ABCA4 variant is typically linked with Stargardt-like phenotypes, while the CEP290 variant is associated with very early onset severe retinal dystrophy. However, in this case, the variants seemed unlikely to explain her clinical presentation.

During a multidisciplinary ocular review, the team concluded that further testing on the RPGR gene (associated with X-linked RP) was necessary. Although the gene had been examined in earlier tests, its challenging open reading frame 15 region was not able to be fully analysed. Further next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches did not identify any issues in this region. However, the team recommended additional testing for copy number variations (CNVs) using MLPA (multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification) and microarray techniques, which can detect gene deletions.

This further testing revealed a deletion of part of the RPGR gene, which explained the patient’s retinitis pigmentosa phenotype. This discovery was crucial for her eye disease management and considerations about family planning.

Key takeaways from this case study

1. Clinical Diagnosis First: While genetic testing is essential, a strong clinical diagnosis is crucial for guiding the genetic testing approach.

2. Comprehensive Genetic Testing: In cases with complex genetic backgrounds, a thorough examination of difficult-to-test regions (e.g., RPGR) and the use of additional techniques like MLPA can uncover hidden genetic causes.

3. Multidisciplinary Approach: Collaboration between geneticists, ophthalmologists, and other specialists is vital to achieve a comprehensive diagnosis, particularly in complex cases.

4. Patient Impact: Identifying the genetic cause of the eye disease had important implications for the patient’s own care and family planning information.

This case highlights the importance of detailed genetic analysis and clinical teamwork in diagnosing rare and complex conditions.

Key steps involved in recommending a patient for genetic testing

1. Ensure Clinical Diagnosis: Start with a thorough clinical diagnosis, considering the patient’s symptoms and history. Genetic testing should complement, not replace, this diagnosis. It is crucial to have a clear understanding of the phenotype before proceeding with genetic testing.

2. Obtain Patient Consent: Ensure the patient is fully informed about the genetic testing process, including potential unexpected findings, such as additional genetic conditions or variants that may affect their family planning or pregnancy options. This is critical to avoid unnecessary anxiety and confusion.

3. Choose the Right Genetic Test: Select an appropriate genetic test based on the suspected inherited retinal disease (IRD). This might involve a gene panel, whole exome sequencing, or other targeted tests. Be aware that these tests may generate large volumes of data, requiring careful analysis by bioinformatics tools.

4. Consider Family History: Take into account the patient’s family history and inheritance patterns, which may influence the type of genetic testing needed. In some cases, you may need to test family members or explore segregation patterns to better interpret the results.

5. Referral to Genetic Services: If the results are unclear or complex, refer the patient to a geneticist or a clinical genetic service for expert interpretation. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussions may be needed, especially in cases with multiple candidate variants or when advanced sequencing techniques are required.

6. Plan for Follow-Up: Prepare for next steps depending on the genetic testing results. This might include consulting with other specialists, considering clinical trials, or offering genetic counseling. If additional testing or techniques are needed (such as MLPA for copy number variations), have a plan in place.

7. Involve Multidisciplinary Teams: Given the complexities of genetic testing, it may be necessary to work with a team of specialists, such as ophthalmologists and genetic counselors, to ensure a thorough evaluation of the results and a coordinated care plan for the patient.

https://retinaaustralia.com.au/now-you-think-this-is-an-ird-whats-next/

Other News

New Board Appointments

Retina Australia directors are thrilled to announce the recent appointment of Associate Professor Anai Gonzelez-Cordero and Dr Alexis (Ceecee) Britten-Jones to the Board. Anai and Ceecee have been long...

First treatment for geographic atrophy approved in Australia

Apellis' SYFOVRE® (pegcetacoplan) TGA Approved Apellis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. announced today that Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration...

2025 Research Grants awarded

Retina Australia is delighted to announce two new Research Grants awarded for 2025. Both grant projects will be focusing on the discovery of potential new...