18 March, 2025

Retina Australia 2025 grant awardee, Dr Jiang-Hui (Sloan) Wang, PhD (Research Fellow), from the Centre for Eye Research Australia, Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, and Horae Gene Therapy Center, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, recently authored a comprehensive review in Molecular Therapy (the official journal of the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy) with Dr. Guangping Gao, a pioneer and world-leader in AAV gene therapy and director of the Horae Gene Therapy Center at University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School. The article published in the Molecular Therapy Journal, “Recombinant adeno-associated virus as a delivery platform for gene therapy: A comprehensive review” (Jiang-Hui Wang et al, Dec 2024), synthesises the latest breakthroughs in retinal gene therapies, including advances in AAV vector engineering, clinical trial updates, and emerging strategies for conditions like Leber congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa.

Dr Wang provides a summary from the patient perspective below.

Latest Advances for Inherited Retinal Diseases (IRDs) and Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

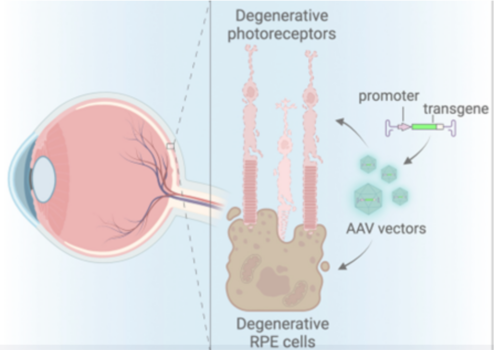

Gene therapy is transforming how we treat retinal diseases by fixing genetic errors or replacing faulty genes. At the heart of this progress is the adeno-associated virus (AAV), a harmless virus modified to act as a “delivery truck” for therapeutic genes (Figure 1). Below, we break down recent breakthroughs, challenges, and what they mean for patients.

Figure 1: This illustration shows the back of the eye, where light-sensing photoreceptor cells (in pink) and supporting retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells (in brown) are damaged. It also shows how a therapeutic gene (transgene) and its control element (promoter) are packaged into AAV (adeno-associated virus) vectors to target and help repair these deteriorating cells.

How AAV Gene Therapy Works

Why AAV?

AAVs are safe, non-pathogenic, and can be engineered to target specific retinal cells. Unlike other viruses, they don’t integrate into human DNA, reducing cancer risks. Most gene therapy clinical trials for ocular diseases rely on naturally occurring AAVs identified in humans and non-human primates.

Key Components

- Capsid: The virus’s outer shell. Different AAV “serotypes” (e.g., AAV2, AAV5, AAV8) target specific cells (e.g., light-sensing photoreceptor cells).

- Gene Payload: AAVs carry a corrected gene or gene-editing tools (e.g., CRISPR) to fix mutations.

Delivery Methods

- Subretinal Injection: Directly delivers AAV under the retina. Effective for outer retinal diseases (e.g., RPE65-LCA), but requires surgery.

- Intravitreal Injection: Injected into the eye’s vitreous gel. Less invasive but struggles to reach photoreceptors. Newer AAVs (e.g., 7m8, AAVv128) are improving this.

- Suprachoroidal Injection: Injected between the choroid and sclera. Emerging method for broader retinal coverage without surgery.

Development of Luxturna: Updates reported at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) 2024 meeting

There is currently only one ocular gene therapy approved by the Therapeutic and Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna®) – targeting mutations in the RPE65 gene associated with retinitis pigmentosa or Leber’s congenital amaurosis.

Safety and Side Effects

- About 62% of patients experienced some eye-related side effects, and 55% had more notable ones.

- Common issues included thinning of the retina, high eye pressure, inflammation or infection inside the eye, cataracts, and thinning of the center of the retina.

- Serious eye problems were seen in 10 patients.

Improved Vision

- Patients showed lasting improvements in low-light vision.

- A special test measuring light sensitivity improved by about 18 units in the first year and remained similarly improved over the next two years.

- Overall, sharpness of vision stayed steady up to three years, even in patients with some retinal thinning.

Real-World Effectiveness

- In a real-life study with 198 patients (average age around 23), the treatment was found to be safe and effective.

- The benefits seen in clinical trials are confirmed in everyday medical practice, with improvements lasting for several years.

Approved and Emerging Retina Gene Therapies

|

Disease |

Cause |

Current therapy |

Key outcomes and details |

|

Retinitis Pigmentosa or Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA2) |

Broken RPE65 gene (prevents vitamin A recycling in the retina). |

*Only ocular gene therapy product approved by FDA: Luxturna (AAV2-RPE65) – Subretinal injection. |

– 65% of patients gained low-light vision (e.g., navigating dim rooms). |

|

Choroideremia |

Faulty CHM gene (causes cell waste buildup) |

AAV2-REP1 – Subretinal injection |

– Phase 3 trial: 5% of high-dose patients gained 15+ letters on eye charts. |

|

X-linked Retinitis Pigmentosa (RPGR) |

Mutated RPGR gene (damages photoreceptors) |

AAV8-RPGR – Subretinal injection. |

– Improved retinal sensitivity (measured by light-response tests). |

|

Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON)

|

ND4 mitochondrial mutation (starves retinal cells of energy).

|

rAAV2-ND4 – Intravitreal injection.

|

– 68% improved vision in ≥1 eye after 2 years. |

|

Achromatopsia |

Achromatopsia |

AAV8-CNGA3 – Subretinal injection. |

– Children: Improved color detection, reduced light sensitivity. |

|

X-linked Retinoschisis (XLRS) |

Broken RS1 gene (weakens retinal structure).

|

AAV8-RS1 – Intravitreal injection. |

– Reduced retinal splitting (schisis) in some patients. |

|

Bietti Crystalline Dystrophy (BCD) |

CYP4V2 mutation (causes toxic crystal deposits). |

AAV-CYP4V2 – Subretinal injection. |

– 46% of patients gained >15 letters on eye charts. |

|

LCA10 |

CEP290 mutation (disrupts cell “antennae” called cilia). |

EDIT-101 (CRISPR) – Subretinal injection. |

– 64% of patients improved mobility in dim light. |

|

Wet AMD |

VEGF protein overgrowth (leaky blood vessels) |

4D-150 – Intravitreal AAV therapy (blocks VEGF). |

– 4D-150: 89% fewer injections needed. |

|

Dry AMD (Geographic Atrophy) |

Unknown (linked to aging + immune system errors). |

GT005 – Subretinal AAV targeting complement genes. |

– GT005: Early signs of slowed retinal damage (development paused). |

Challenges and Solutions

1. Immune Responses

- Pre-existing Antibodies: Up to 50% of people have antibodies against common AAVs (e.g., AAV2). Newer engineered AAVs (e.g., P2-V1) evade these antibodies.

- Inflammation: Steroid eye drops often manage post-injection inflammation. Suprachoroidal delivery may reduce this risk.

2. Limited Gene Size

AAVs can only carry genes <4.7 kB. For large genes (e.g., CEP290 in LCA10):

- Dual AAVs: Split the gene into two parts that recombine inside cells.

- CRISPR: EDIT-101, a CRISPR therapy for CEP290, successfully restored vision in 64% of LCA10 patients in early trials.

3. Targeting Specific Cells

- Capsid Engineering: Machine learning designs AAVs with enhanced retinal penetration (e.g., AAVv128 transduces photoreceptors via intravitreal injection).

- Promoter Selection: Cell-specific promoters (e.g., rhodopsin for rods) minimise off-target effects.

4. Durability

While therapies like Luxturna show long-term benefits, photoreceptor loss may progress. Combining gene therapy with neuroprotective drugs is being explored.

What’s Next?

CRISPR and Base Editing:

- EDIT-101: Removes a mutation in CEP290 causing LCA10. Early trials showed improved vision and mobility.

- Prime Editing: A newer, more precise CRISPR variant is being tested in animal models.

AI-Designed AAVs:

Machine learning analyses data from primate studies to create capsids with better targeting and lower immune triggers.

Accessible Delivery:

Suprachoroidal injections (in-office, no surgery) are advancing for diseases like diabetic retinopathy.

Key Takeaways for Patients

- Genetic Testing is Critical: Knowing your specific mutation helps match you to the right therapy.

- Early Intervention Matters: Trials for achromatopsia and LHON suggest better outcomes when treated early in the disease.

- Combination Therapies: Future treatments may pair gene therapy with anti-inflammatory drugs or neuroprotectants.

- Stay Hopeful, Stay Informed: Over 70 trials are active globally. While not all succeed, each teaches us more about curing blindness.